From Dead Language Society, an explanation for why the English language doesn’t use diacritics even though French does. It’s ironically because of the French.

Transferring an image onto lino using alcohol

There is tons of advice out there for how to transfer an image onto lino for carving and most of it doesn’t work when you need it to. There are unaccounted for variables that make one process work for person A but fail for person B. Maybe humidity? Slight differences in the printer? Who knows. Here’s one more technique that you can try after you’ve tried everything else: rubbing the back of the print with alcohol. I got the idea after I saw someone mention that they use “colorless blender,” which I took to mean the marker that you use to blend together marks from other markers. Blending markers like Copic are alcohol-based, so I figured I could try the same technique with cheaper rubbing alcohol.

It’s faint, but it worked! I used a Brother toner printer which has been printing kind of cruddy lately; no matter. I clipped the print to the lino to hold it in place. I used a paper towel to saturate the back with rubbing alcohol, then I laid wax paper on top to protect it and rubbed it down into the lino with a barren. (On his channel, DAS Bookbinding refers often to “rubbing paper,” meaning butcher paper or parchment paper that can be used to protect a more delicate wet paper or fabric from wrinkling or getting dirty when you are rubbing out the air bubbles.)

Next I will experiment with different colored coatings on the lino to see if a different surface might help the image transfer better.

Recent Links

Call Me Comrade – Miriam Dobson – London Review of Books – During the Cold War, there were groups that encouraged letter writing between American housewives and Soviet women. Interesting look into the ways this changed the letter writers.

Fergus Macintosh, lead fact checker at the New Yorker, interviewed by Merve Emre – Fascinating. I thought I knew in a general sense what a fact checker did, but I didn’t realize the extent. There’s also an exercise in examining a sentence to find all the things that you think should be fact checked in it.

An exercise in creating art in the style of Bill Beckley – celine nguyen – try it yourself!

London’s Low-Traffic Zones Cut Deaths and Injuries by More than a Third – The Guardian – We have a few of these in the city, but they are all in places where traffic would already be low. The only places that drivers will allow them are places where drivers don’t go in the first place, usually neighborhood streets that are not through streets so the only traffic is from the 20 or so homes on the block. The article talks about a similar study of speed limits where it describes 20 mph as a slow, safe speed limit. If I go 17 miles per hour on my bike, someone will complain that it’s dangerous for pedestrians, but 20 in a car is perceived as “safe.”

Now available on Jstor, the digitizied diaries of the only woman, serving as a stewardess, on an 1890s steam ship.

José R. Ralat at Texas Monthly is the world’s only (known) full-time Taco Editor. One of the common questions he gets is how he does the job in Texas without driving.

Recent Links

But books actually are my entire personality — S. Elizabeth from Unquiet Things discusses the changes in the way reading is perceived now versus in the 80s and 90s, and what it means for reading to be more than a hobby.

What do you expect? – Gavin Francis – Covers two recent books about placebos. Here’s an interesting tidbit: “We know that expensive placebos work better than cheap ones, capsules work better than tablets, and colored capsules work better than white ones. Blues and greens work better as sedatives, while pinks and reds work better as stimulants and painkillers. (Unless you’re an Italian man: Howick notes that blue is stimulating for Italian men, perhaps because the Italian soccer team wears blue.)”

A thread showing the best Gacha machines in Japan – Worth dealing with Bluesky’s terrible thread navigation.

My “to read next” pile

Recent Links

Remember that brief period in 2020 when we knew enough germ theory to realize that Covid was airborne and we needed face coverings, but not enough to realize that germs were extremely small so we needed surgical-level face coverings? This Reddit thread compiles some of the improvised masks that people used for grocery shopping in those days.

’Occupation: Organizer’: How Anti-Politics Becomes Anti-Democracy, by Emma Tai in Convergence. A warning against ACORN-like political structures that don’t allow democracy to flourish within the organizaiton.

Lowell’s Forgotten House Mothers, by Sarah Buchmeier – A review of what we know about the boarding house keepers who were vital to the functioning of the Massachusetts company towns in the 1800s. We don’t know much!

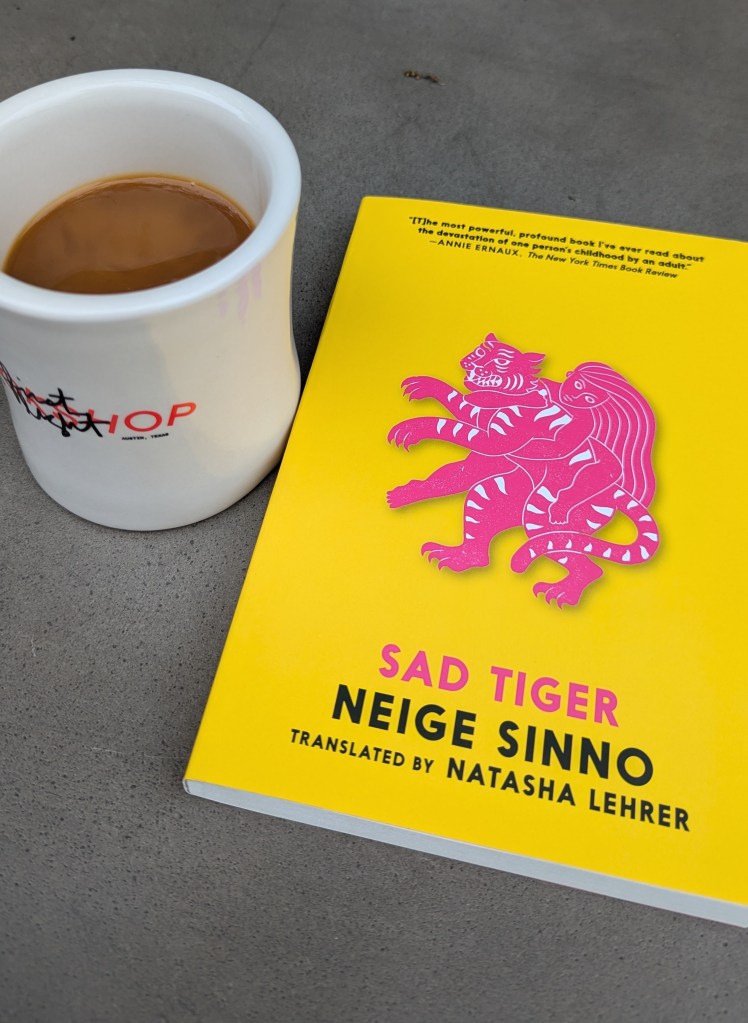

What I’ve been reading

(Despite the photo, I have NOT been reading Sad Tiger. I picked up my pre-order and saw it described as “devastating” and was not ready for it.)

First Love by Ivan Turgenev, translated by Isaiah Berlin

The Mookse and Gripes podcast has started a novella book club, and this is the first selection. It’s an experiment in using Discord to collect former book twitter folks into a reading group. It’s also an experiment, for me, in slowly reading a novella. This could be read in one sitting but instead it’s being spread out over a week. I read the first third and had to pause myself from reading further.

Notebooks by Tom Cox

I haven’t had time lately because my mornings are now used for exercise, but I used to have a “morning book” that I read a little bit of every day before writing in my journal. It was usually diaries or something similar, and I would spend a bit time examining how other people process their lives before processing mine. Notebooks sort of fits that theme. It’s excerpts from Cox’s notebooks, so it’s real like a diary but the excerpts are more like tweets. They are short quips, with an occasional longer bit that might take up a whole two paragraphs. It’s hard to read in long chunks for the same reason it would be hard to sit down and read someone’s twitter feed all the way through. Each individual bit, however, is a delight with hilarious stories about mischievous Devon hedgehogs and the antics of his dad WHO TALKS LIKE THIS.

Strike! by Jeremy Brecher

Ok, I haven’t really started this one yet. My local DSA chapter is about to start reading this history of American strikes alongside The Troublemaker’s Handbook. I am a little less enthusiastic now that Shawn Fain is out there making the labor movement look bad, but I do want to be more educated about the subject for the next time I get into an argument about “why don’t Americans call a general strike?” I might not actually manage to read my assigned bits before we meet, but the DSA bookclubs are the sort where the discussion the books prompt about current conditions is the vital part.

Butter by Asako Yuzuki, translated by Polly Barton

This is the book that I’m actually reading in the sense that I carry it around with me everywhere and dip in as time allows. I picked it up on a whim at the bookstore when I saw Barton’s name and the cover blurb. Rika is a young female journalist at a publication that has never had a woman writer. She works long hours to become the first, neglecting her own love life and comforts, eating only 7/11 onigiri and grab-and-go salads. In an attempt to get an exclusive interview with a former food blogger, Kajii, accused of murdering men she met on dating apps, Rika starts to follow Kajii’s orders about what to eat and cook. From prison, Kajii gives Rika assignments such as to bake a quatre-quarts and serve it to a man while it is still hot from the oven. Rika begins to embrace the sensuality of food in a way she hadn’t before, but also gains weight, forcing her to confront the extreme fatphobia and misogyny of Japan. The ways the case transforms her life aren’t straightforward, and about two-thirds of the way through, this novel takes a different direction which pleasantly surprised me after I had been lulled into a routine of jailhouse interviews and baking. I still have at least a hundred pages to go, but I feel like I am in good hands with Yuzuki and Barton.

5 Things Regular Drivers Might Not Know About Cyclists

- At stop lights, we flirt with our fellow cyclists. We compliment each other’s bikes. Or sometimes we just say “hello” or let them know their shirt is on backwards. Personally, I engage in many passive aggressive undeclared races with cyclists who are rude. The point is that we are sometimes interacting directly with other cyclists, as part of a community. We are not isolated from one another, or from the consequences of our behavior. (But seriously, more people flirt with me when I am on my bike than at any other time in my day.)

- We can feel the paint on the road. We are sensitive to road conditions like debris that a driver wouldn’t even be conscious of. If you wonder why a cyclist is in the car lane instead of what appears to be a perfectly good bike lane, it’s likely because there are dangers in the bike lane that aren’t apparent to drivers. For instance, a pile of leaves can conceal dangerous glass or holes, so it’s best to avoid them altogether.

- We see a lot of broken glass and car parts at intersections. We see curbs that have been destroyed by vehicles that don’t stay in their lanes. We see more of the effects and frequency of poor driving than drivers do.

- We are not expected to follow the law (by traffic engineers). A cyclist has trouble following traffic law 100% of the time because, for cyclists, those laws are poorly-defined and in flux. For instance, on my morning commute there is a light that triggers when cars pull up to it. It doesn’t trigger for my bike. I have to run the red light if no car shows up to save me. Engineers have considered this when installing the light and decided it was ok. There are areas of town where according to the city, cyclists are not allowed to ride on the sidewalk. Some parts of this area also have road paint indicating that cyclists should ride on the sidewalk for a block and then abruptly hop back onto the bike lane. Sometimes the bike lane suddenly switches to being on the left side of the road, and I have to merge across three lanes and ride on the left before having to merge back right and ride on the right. Sometimes safety takes priority over either indicators or laws. It’s safer for pedestrians and cyclists to cross a street slightly before the light turns green for drivers. Many intersections will flash the walk sign for pedestrians a few seconds before the light turns green. As a cyclist, do I wait for the light to turn green or do I cross with pedestrians? Do I follow written laws, or do I follow the road indicators installed by traffic engineers? Or in cases when neither is safe, do illegal but safer for everyone near? Cyclists constantly have to make their own decisions about when to follow the law.

- There are more of us than you know because we’re deliberately riding on roads where you won’t encounter us. When I first started commuting to my current office, I took the direct route. Not necessarily the one a driver would take, but still using whichever major roads had bike lanes. Over time, through experimentation and talking to other cyclists, I landed on a route that zig zags through residential neighborhoods and parking lots, selecting for quiet and well-paved paths. I see many other cyclists on this circuitous route; apparently they have discovered the same paths I did and made the same choices. The only drivers who see us on this route are homeowners along the path. Other drivers would not be aware of how many workers are commuting by bike every day because we’re deliberately hidden.

Recent Links

Bluesky thread on why the Carlisle 52 is the best drinkware in America. I know the Carlisle as “the cups they have at Mr. Gatti’s.”

Students studying at the library… but studying the graffiti they find from previous students.

I had just finished reading A Ghost of Caribou by Alice Henderson when I found this article. A Ghost of Caribou is an eco-thriller about a biologist studying a rare species of caribou. It’s endangered because it can only survive with extremely old lichen that grows in old growth forests. An old growth forest is usually well over a hundred years old. This article is about researchers in the UK asking, “is there a way we can make trees older, faster?” It involves gleefully harming trees, for the greater good!

Profile of the philosopher Martha Nussbaum and some of her work.

How to do something

I have been feeling so helpless lately, and that’s not usual for me. Being locked into my very effective local DSA chapter, I usually feel like there’s a way I can contribute. Everything now is so overwhelming that nothing feels like it’s enough.

Maybe you feel the same way. Maybe you live in a rural area and can’t even make it down to one of the many Tesla protests. If so, here’s an action you can do from your home. Libraries for the People, a leftist libraries advocacy group, needs volunteers to gather data on library boards around the country. If googling library boards and maybe calling for more information sounds like something you can do, scroll down on this page to Research Support for more information.

You can find other suggestions for things to do ranked from easy to hard in this guide from The Disruption Project.

One of my friends was surprised to hear that there were multiple protests going on around town. He hadn’t heard about them, which seemed like a failure in the advertising of the protests to him. If you’re not on social media—maybe you’re one of the people who recently dumped Instagram and FB after Meta’s increased technofascism—how would you hear about a protest? You’d have to be a deliberate part of a group that’s communicating events to members or have a friend who is doing the research for you as part of a group and then sharing that information directly. This isn’t extremely efficient, especially given the time sensitive nature of many actions. I think more people should leave social media, so this problem of how to learn about mass events is one that I am chewing over.

If you are in Austin, here are some groups you might join to find out about these events:

- Austin DSA

- Your workplace union – If you are a worker, you have a modicum of power in capitalism. Don’t leave that power on the table. If you don’t have a union yet, you can get advice and support from the Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee.

- Indivisible Austin – they would not be my first choice because they are only activated during crises and maybe we could have avoided those crises if they were, for instance, preemptively working with Austin DSA to keep Tesla from moving to Texas in the first place. They are extremely active right now, though.

- Austin Justice Coalition

- Former council member Jimmy Flannigan has started a mailing list to connect people and was one of the primary promoters of the recent Tesla protest. You can sign up at https://www.jimmyflannigan.com/the-work-2-0/